This free script provided by

Dynamic Drive

Don't forgot to check ReserveBooks.com reviews and books every day.

We specialize in rare book reviews and avoid the publication of promotional book reviews. To have your book reviewed, mail a copy to us (see contact page).

Reviews - Cook Communication

THE RAT’S TALE AND ITS WINDING WAYS:

A REVIEW OF BIYI BANDELE’S ‘BURMA BOY’

By

Henry Chukwuemeka Onyema

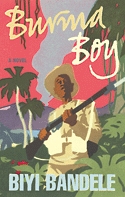

Title: Burma Boy (Novel)

Author: Biyi Bandele

Publishers: Jonathan Cape (Britain) 2007

Farafina (Nigeria) 2007

Number of pages: 216

The first half of the rather long-winded title for this piece was inspired by a story narrated by the novel’s protagonist, Ali Banana (p.42) and the book’s short and somewhat brutal epilogue. Like a record stuck in the groove those lines: “That is all. Off with the rat’s head” continues to reverberate in my head long after my heart was pierced by the closing scene where another significant character, Bloken, encounters the death-maddened Banana.

Maybe I am more personally involved in this novel than some readers. As a professional historian who teaches the subject (where there are students) and allied subjects like Government and Social Studies to a generation who see the world through Western especially American spectacles, talking about the brave Africans who bore the British Empire on their shoulders between 1939 – 1945 when Hitler, Hirohito and Mussolini kidnapped the cosmos sounds antediluvian. Cold history, even when permeated by the warmth of real-life relics, does not cut any ice for people caught up in a jet-flying world of Microsoft, Tantalizers, Dow Jones, and hip hop. Do not blame the youngsters; are we, so-called adults, any better?

For far too long the story of Nigerians who gave their today for the Union Jack’s tomorrow during World War Two has been astonishingly ignored, defaced, even put in the worst human condition-oblivion. It is not as if these heroes are unknown. Historical records abound. Some of them are still alive, enfeebled but unbroken. Literature, mostly penned by foreigners, recognizes them in passing.

It took a son of one of these heroes in the person of Biyi Bandele to up the ante. Bandele performed the ultimate literary magic: painting a wide portrait of amazingly human and thus believable characters performing in one of the most disorientating theatres of humanity: the battlefield. All of them are heroes, from the one-eared Sergeant Damisa to the hairless Bloken to the seemingly crazy Japanese who think nothing of throwing themselves through mined perimeters. But Bandele’s brand of heroism is unique because it gets under the skin and souls of the heroes. These are no gun-toting jungle experts performing Arnold Schwarzneggar feats or an African cast for a remake of Steven Spielberg’s “Saving Private Ryan.” These are real, “blaady maadafucking” (to paraphrase Bloken) human beings who are not above wetting their trousers at the crack of a rifle, despite months of rigorous training.

The novel is a subtle quest for human identity, a seeking for one’s essence of life, even in the valley of bones and sea of blood. Bandele never tells us but I strongly believe that the eccentric, Atabrine-addicted Major Orde Charles Wingate realized his life’s mission when his fecund, fevered brain gave birth to the unorthodox, deep penetrating, long-range military unit called the Chindits. Call Ali Banana’s hunger for Burma action sheer youthful exuberance, if you like. But though the looming spectre of combat subdued his heart, it was in the heat of war’s hellish savagery that he found his manhood when he shot his beloved and incapacitated Damisa (pp.198 – 203). But at what price? Do not answer till you have read the novel.

Most of the characters reflect a tragedy that haunts Africa till date: warring for causes about which we know little or nothing. Over sixty years have gone by since the guns of World War Two fell silent, but in my opinion, it is still new style, old dance for succeeding generations of Ali Bananas, Guntus, Godiwillin, etc across Africa. How many of the callow lads who slaughtered each other during the Nigerian civil war know why they did it? How many of the cocaine crazed children combatants of Liberia and Sierra Leone understood the issues at stake, if any? What of the Rwandaese? Of course, there are different situations. e.g. the liberation struggles in South Africa, but by and large, the truth is that the clash of claims and counterclaims really meant little to many baby soldiers it spawned on the face of Africa. The wind blew them into what they knew not, and when it ended, the survivors discovered that both the falcon and falconer had gone deaf and dumb.

Holy Joes may criticize “Burma Boy” for its seeming homage to vulgarity (see the exchange between the Nigerians and the Japanese-one of my favourite portions of the novel-pp. 164 – 166; and Danja’s vow to initiate Banana into the sweet-sour world of sex. pp 188- 190). But that is what makes Bandele’s novel a cracking yarn: telling it as it is. Fighting troopers worldwide demand the rude relief of the battlefield, and vulgarity is at times refreshingly expressive of the heart’s true pulse. What transpired in pp. 164 – 166 is not unusual in the madhouse of war. Ever heard that, at the height of the Nigerian civil war, Nigerian and Biafran troops, fagged out by the senselessness of the whole thing, occasionally got together for football matches and the type of parties where booze and breasts were generously supplied?

Though “Burma Boy” is no “Beasts of No Nation”, Bandele’s skill at ‘crippling’ turenchi (English language) with rich Hausa flavour is impressive. Given the novelist’s deep rootedness in Hausa language and culture, though a Yoruba by birth, this is not surprising. But his code mixing and code switching is so accessible that it gives “Burma Boy” an identity peculiar to it. Thus you need not employ a Hausa translator to know that “Samanja” is Sergeant, “Farabiti” is private, “Janar” general etc. The humour leavens the tale with flashes that help us take the awful bullets and disease without choking on our pain and puke.

The striking off of the rat’s head might have ended Banana’s story but the epilogue of ‘Burma Boy’ only marks the beginning of a vicarious journey with these miserably human heroes whose account reverberates in our consciousness in many ways, either as a simple war adventure novel or something deeper.

Henry Chukuwuemeka Onyema (also spelt Onyeama) is

a teacher and award-winning writer.

He lives in Lagos, Nigeria.

Henry’s postal address: P. O. Box 3799

Mushin Post Office,

Lagos State,

Nigeria.